3 Steps to say goodbye to reading glasses for good

Restoring clear vision is easier than you might think. Follow this simple path to a life without the inconvenience of reading glasses

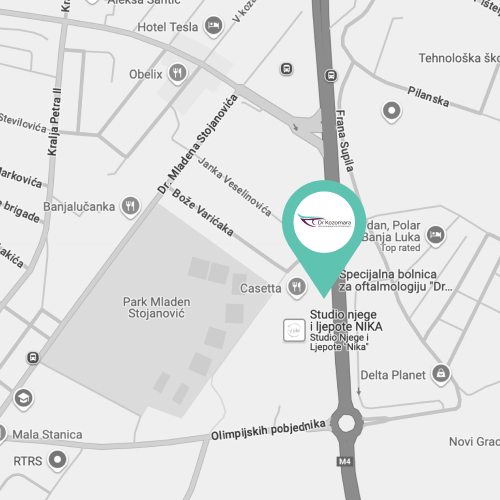

Step 1: Reach out

Not everyone is eligible for treatment to eliminate the need for reading glasses. The first step is to find out if there’s an option that can help you. Call our friendly team at +387 51 439 591, or book an appointment using our easy online kalendar.

Step 2: We'll meet

During your appointment, we’ll discuss your specific vision needs and lifestyle preferences. You’ll get detailed answers to your questions and a personalised recommendation for your vision correction. You’ll leave with a clear plan and the confidence to make an informed decision.

Step 3: FEEL YOUNGER

After treatment, patients are often surprised by how quickly their lives improve and how much younger they feel. Reading menus, checking phones, or driving becomes effortless again. Many wish they had done it sooner!

A tradition of excellence in eye care

Leading the way in innovative treatments and personalised care for over 15 years

Are reading glasses holding you back?

If so, you might want to consider lens replacement surgery

Always misplacing your glasses?

Do you constantly search for your reading glasses? Whether it's checking your phone, reading a menu, or working on your computer, your glasses always seem to disappear when you need them the most. By scheduling an appointment, you can explore options to free yourself from this inconvenience. Imagine a life where you never have to worry about where your glasses are again.

Feeling eye strain?

Do your eyes feel tired after focusing on small print or screens? Eye fatigue is common as vision changes with age, especially if you rely heavily on reading glasses. Booking an appointment could help you discover ways to reduce this strain and enjoy a more comfortable viewing experience.

Finding it hard to stay updated with technology?

Switching between glasses for different tasks can make using devices frustrating. Trying to read small text on screens and constantly swapping glasses interrupts your flow. By scheduling an appointment, you can explore solutions that make it easier to stay connected in today’s digital world, offering you a smoother, hassle-free experience.

Join thousands who have achieved freedom from glasses and contacts

Learn how they overcame their dependence, and find out how you can, too

We have replaced the images of the actual patients who provided these testimonials to protect their privacy

Affiliations and memberships

We are proud to be a part of these professional bodies

Hi i'm Dr. Bojan Kozomara

With over 20 years of experience and a PhD in Ophthalmology, I am proud to be a leading expert in eye health.

As the Director of the Special Ophthalmology Hospital "Dr. Kozomara," I have performed numerous successful surgeries, specialising in vitreoretinal and phacoemulsification procedures.

My commitment to personalised care and deep expertise allow me to provide trusted, high-quality treatment.

My greatest reward is seeing my patients thrive with improved vision.

Dr Kozomara